On January 6, 2021, I awoke to the news that Rev. Raphael Warnock and John Ossoff, powered by unprecedented Black voter turnout, had won the Georgia Senate runoff, a political game-changer for Georgia, the nation, and the world. Events later that day would overshadow that victory, yet because of the bravery of many did not negate it.

The Georgia election was personal to me beyond its implications for the policies my values compel me to support. Both senatorial candidates who won had spoken to the progressive faith that drove their policies. Faith in Public Life, the organization I founded and was leading then, had been part of a statewide effort to engage voters and protect access to the ballot. Rev. Warnock is an esteemed friend. Georgia is my home state, the state I once left to find myself, and I could now see myself returning to because of such wins.

I was celebrating as I prepared for a 1:30 interview from home with the Washington Post. “Finally,” I thought, “a progressive faith victory. Maybe we can yet capture some of the moral influence it had in the days of Civil Rights and labor movements.”

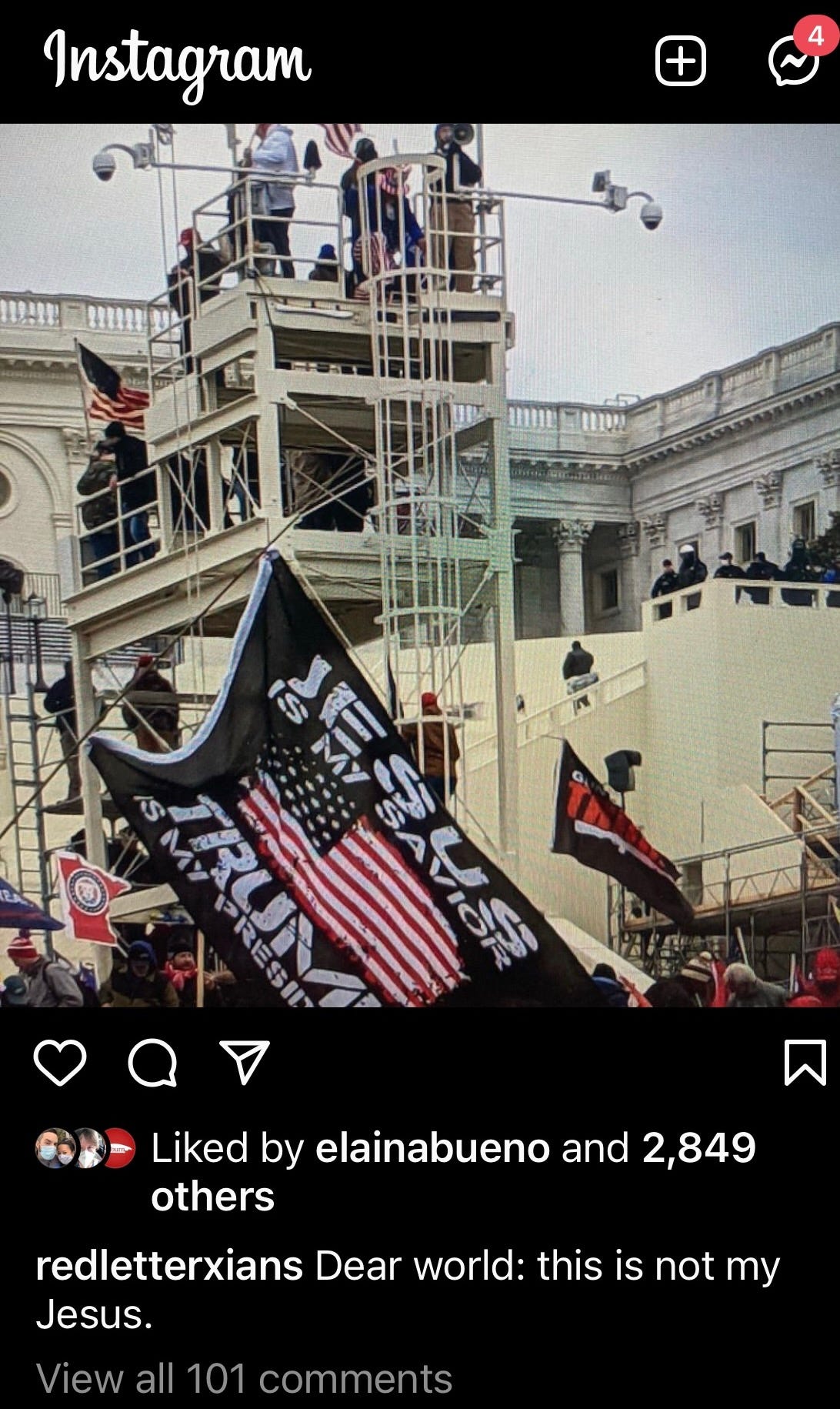

After the interview, I went downstairs to watch live coverage and celebrate this victory. Instead, what I found was an attack underway on our nation’s capitol, just miles away from where I sat, with Christian flags flying above the crowd.

I realized instantly that I was witnessing the culmination of 40 years of Christian nationalist organizing– the emergence of an idolatrous faction resorting to violence to cling to power illegally.

Until that moment, it was hard to picture what a civil war would look like here in the U.S. The insurrection clarified that. So has my recent reading on how civil wars start.

While civil wars until the 90s were provoked by competing political ideologies and carried out by militaries, today’s civil wars result from a more gradual process of factionalization around religious and ethnic identities and are carried out by home-grown militias.

Factionalism is an acute form of political polarization. It happens when political parties become based on ethnic, religious, or racial identity rather than ideology. Parties then seek to rule at the exclusion of others. A superfaction is when groups line up not only around ethnic or racial identity but also around religion, class, and geography. According to conflict experts, the appearance of a superfaction is the strongest indicator of a potential civil war.

As society factionalizes, people are forced to choose sides whether they want to or not. If they don’t choose a side, they may become a target of violence or deprivation of power or resources. The center cannot hold. Those who do not want violence or who might be open to dialogue are forced to choose a side.

What we see in the largely white, evangelical, and Southern Trump faction began in the 70s when political operatives in the Republican Party appealed to white Christian grievance in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement. School desegregation, including the IRS revocation of tax exemption from discriminatory Christian private schools founded to support white flight, was the foundational issue that launched the Moral Majority. Over the years, more white Christians were brought in via abortion and LGBTQ equality – issues that were not a heated issue until the Right made them so.

Perhaps this decades-long project could have been countered, but that’s a topic for another day. If I had a time machine (A TARDIS for you sci-fi fans), I think I know where I'd plop down.

Where do we go from here?

I connected recently with a leader in the Republic of Georgia, a few time zones away from my eponymous home state. Dr. Malkhaz, the Metropolitan Bishop of Tbilisi, described a similar factionalization in Eastern Europe. He explained to me that Christians there weren’t disparaging LGBTQ communities until Putin “turned on the spigot of hatred” around 2013. Until then, people either thought little about the issue or were tolerant of LGBTQ people. In the Bishop’s view, Putin was merely using the issue to distract, spread fear, and align Georgia against the West and with Russia. It’s one more tool, in addition to attacks on religious and ethnic minorities, that can be used to create a faction that is anti-democracy.

Engaging socially conservative faith communities isn’t inherently authoritarian. It can be a tool for inclusion. From 2005 to 2015, Faith in Public Life built common cause with social conservatives around issues like immigration and healthcare, which led to our finding common cause even on issues like abortion and LGBTQ rights, which led to policy victories against discrimination in employment and housing based on sexual orientation or gender identity. That collaboration held through the Trump years, but bringing new leaders into the fold became harder.

Autocrats seek to make such coalition-building impossible. They attempt to monopolize and wield religion to build factions. That’s why autocrats like Victor Orbán gradually restrict the freedom of civil society organizations that use religion to bridge rather than divide.

Can religious leaders unite globally to interrupt what is essentially now a global polarization along the lines of the U.S. culture war? I’m about to launch Faith in Democracy, a global network of religious leaders committed to preserving democracy as the best way to fulfill our core religious commitments to the dignity of all human beings. Can it be done? My conversations around the world suggest world leaders are eager to try. We have a lot to teach one another.

Understanding how factionalization happens is key to stopping it. In How Civil Wars Start, Barbara F.Walter writes that the CIA established a Political Instability Task Force in the early 90s that can predict with a fair amount of accuracy who is on the brink of a Civil War.

Get this: the CIA task force has an algorithm for predicting a civil war.

The building blocks include rigid and competitive political parties the same size, a party that revolves around a dominant figure who appeals to ethnic or religious nationalism, negligible party platforms, and rallying around identity-related words and symbols.

The spark that lights this kindling can be a weakness in the governing regime or, say, a demographic change that heightens grievance or vulnerability.

Alarm bells ring when the “dominant figure” emphasizes their group’s separateness and grievance and finds ways to encourage militancy and escalate tensions. They might establish or encourage militias. Their rhetoric grows increasingly violent and apocalyptic.

A good example can be found in Trump’s campaign speeches about wanting to be a dictator from day one, wanting to free the insurrectionists who he claims are persecuted, and even wanting even to pardon the militias that led the violence on January 6th.

In all the literature, religion and ethnicity are listed as key elements to factionalization, but religion, I find, gets short shrift in the studies and proposed solutions. I’m thinking about why this is the case. But I’d say a good part of that is that in our embrace of pluralism, we saw religion too often as a regressive force working against pluralism rather than a force for good that could enhance pluralism.

I see where the confusion comes from. But I also am convinced that until we fully engage religion and support pro-democracy religious leaders, bad actors will get the best of us by funding those who misrepresent religious teachings for personal gain.

If there is an algorithm for predicting conflict, let there be one for transformative religious organizing that leads to democracy.

I’d say the variables in the algorithm to resolve factionalism involve building relationships across the globe, across religion, race, and sexuality, as well as reclaiming our faiths for dignity out of the clutches of those who use them to spread hatred, fear, and discrimination.

I’ve seen religious communities swing the difference in favor of protecting vulnerable populations and advancing the well-being of all. This year, I look forward to thinking with you about how we do that together globally.

Drop me a note in comments:

If you had a time machine (TARDIS), what intervention in history would you make to interrupt the factionalizing of religion?

When it comes to interrupting factionalization, what do you see working (no idea or example is too small to share)?